Dental practitioner involvement at head and neck cancer multidisciplinary meetings in Australia

Introduction

Multidisciplinary care (MDC) and teams (MDTs) have long been endorsed as the gold standard of cancer care, with increasing evidence identifying this as instrumental in providing best-practise treatment and optimal patient outcomes (1,2).

The diagnosis and management of head and neck cancer (H&NC) requires streamlined coordination of care given the time-sensitive nature of the disease and the involvement of multiple teams (1). To work effectively, open and clear lines of communication must exist between all team members involved in patient care, with a treatment framework and timeline provided in the pre-, peri-, and post-treatment periods (2-6).

Variation of MDC allows for tailored approaches, however, several principles hold across all pathologies and healthcare settings (3):

- A team approach, involving core disciplines integral to the provision of good care, including general practice, with input from other specialties as required;

- Communication among team members regarding treatment planning;

- Access to the full therapeutic range for all patients, regardless of geographical remoteness or size of institution;

- Provision of care in accordance with nationally agreed standards;

- Involvement of patients in decisions about their care.

The degree to which MDC is implemented in practice varies widely across geographic locations, hospitals, and healthcare settings, with MDT attendance varying significantly. Australia and New Zealand centres have significant variations in H&NC MDT attendance of medical specialities, dental specialities, and allied health (7). This is supported by the authors’ observations working at various institutions and being involved in H&NC MDT meetings. The benefits of adopting a multidisciplinary care team approach include (3,5-7):

- For patients:

- Increased survival for patients managed by an MDT;

- Shorter timeframes from diagnosis to treatment;

- Greater likelihood of receiving care in accordance with clinical practice guidelines, including psychosocial support;

- Increased access to information;

- Improved satisfaction with treatment and care.

- For health professionals:

- Improved patient care and outcomes through the development of an agreed treatment plan;

- Streamlined treatment pathways and reduction in duplication of services;

- Improved coordination of care;

- Educational opportunities for health professionals;

- Improved mental well-being of health professionals.

Dental assessment and treatment before, and during the management of H&NC, has been shown to improve patient outcomes, improve oral rehabilitation, and manage radiation-related side effects like osteoradionecrosis (ORN) (8-13). Pre-treatment dental assessments aim to identify oral and odontogenic diseases and implement appropriate timely treatment for adequate healing before surgical and adjunctive oncological therapy (9-12,14).

Due to the lack of regular presence of dental practitioners in the hospital environment, dentists are neglected from routine MDT attendance with patients requiring a separate referral pathway for assessment. As a result of this, and due to the time-sensitive nature of H&NC, arranging pre-treatment dental assessment is often overlooked or unable to be facilitated promptly. The absence of routine dental review pre- and post-treatment puts patients at greater risk of negative oral health outcomes such as ORN (9-12). Long-term deficits can impact patients’ ability to chew, maintain weight, speak, and their quality of life and long-term survival (12,13,15). To date, there is a paucity of published data on the specific attendance rates of dental practitioners at H&NC MDTs, and the potential impact this has on patient outcomes on a societal level.

Objectives and aims

This study’s aims are outlined below and focus on investigating the attendance and overall role of dental practitioners in H&NC MDTs within Australia and New Zealand. In addition to this, the attendance of other medical and surgical specialities as well as allied health staff will be presented, neither of which has been done before. This intends to address concerns regarding routine attendance of H&NC MDTs by dentists in the future, ideally improving rates of ORN and overall oral health for their patients.

- Assess the attendance of Australia and New Zealand H&NC MDTs by medical, dental, and allied health practitioners;

- Identify the rate of H&NC MDTs attendance by a dental practitioner;

- Describe the role of dental practitioners within H&NC MDT (e.g., reviewing of imaging, pre-surgical oral assessment, management of mucositis and conditions after surgery/radiotherapy, restoration of dental implants);

- Identify the rate of ordering of orthopantomograms (OPGs) and review at H&NC MDT;

- Describe referral pathways for dental review prior to surgery and follow-up protocol post-operatively/post-radiotherapy.

The study is reported according to the SQUIRE reporting checklist (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-53/rc).

Methods

This project was designed as a cross-sectional observational study and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Ethical Exemption was applied through, and endorsed by, the Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee, HREC Reference EX/2023/QTDD/100748. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for the publication of this article.

H&NC MDT participants were identified on the Australian and New Zealand Head and Neck Society (ANZHNCS) website, as well as local knowledge of additional non-listed MDT sites. A mixture of staff from Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) departments, Dental Practitioners, and both clinical and non-clinical nurses completed the provided survey. The contact information provided by the ANZHNCS primarily were for nursing staff who worked as Clinical Nurse Consultants and Coordinators, or ENT surgical trainees/residents. Further escalation to clinical staff was made by the initially contacted individual based on their confidence in their ability to be able to complete the survey. Consent was dealt with on an individual basis by the participants, with formal consent obtained through additional discussion with relevant organisations’ representatives and written confirmation via email correspondence within two weeks of the initial email. If no email address was listed, coordinators were contacted via phone inviting participation into the study with the same wording as the initial email and requesting a corresponding email to send the participation email and survey (Appendix 1). Survey questions were developed in consultation with clinicians involved in H&NC MDTs as both dental and non-dental practitioners. A follow-up email was sent after two weeks if no response was heard prior. Collection periods occurred between August and September 2023, and due to an initial poor response, an additional period occurred in May 2024.

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed to summarise collected surgery data, with figures and percentages calculated for categorical variables (e.g., attendance rates of specialities) and data displayed and analysed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.59).

Results

Forty centres from Australian and New Zealand health services with H&NC MDTs were contacted, with 21 Australian centres returning completed surveys for analysis. Of these 21 centres, 19 (91%) had dental practitioner involvement and established referral pathways for patients to access pre-treatment review and management. These pathways involved direct referral from outpatient clinics or from the MDT itself, with referrals being to a mixture of public and private centres. Table 1 shows that 12/21 (57%) centres had routine dental practitioner involvement post-treatment, particularly for oral rehabilitation including dental implants, with the remaining 8/21 (38%) centres stating that referrals to external public or private sites occurred on a case-by-case basis. Ten (48%) centres routinely organised OPGs for their patients, with 8/21 (38%) additional centres specifying that they were organised on a case-by-case basis. This was inconsistently performed within and between states. Six (29%) centres monitored rates of ORN.

Table 1

| State | Chairperson | Dental practitioner attendance | Subspecialty attendance | Utilisation of OPG | Oral rehabilitation/implants & prosthetics | ORN reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | RONC: 2; ENT/head and neck: 1; head and neck/RONC: 1 | 3/4 (75%) | ENT: 4; head and neck: 3; PRS: 4; OMFS: 1; RONC: 3; MONC: 3; radiology: 4; nuclear medicine: 1; palliative care: 1; anaesthesia: 1; pathology: 2 | 3/4 (1†) (75%) | 3/4 (1‡) (75%) | 2/4 (50%) |

| Victoria | ENT: 5; ENT/MONC/RONC: 1 | 6/6 (100%) | ENT: 6; head and neck: 2; PRS: 6; OMFS: 4 (1†); RONC: 6; MONC: 6 (1†); radiology: 3; nuclear medicine: 2; pathology: 3; neurosurgery: 1 (1†) | 3/6 (3†) (50%) | 5/6 (3‡) (83%) | 2/6 (33%) |

| South Australia | OMFS/ENT/RONC/MONC/PRS: 1; ENT 1 | 2/2 (100%) | ENT: 2; PRS: 2; OMFS: 1; RONC: 2; MONC: 2; radiology: 1; nuclear medicine: 1; palliative care: 2 (2†); pathology: 1; high-risk physician: 2; dental practitioner: 2 | 2/2 (1†) (100%) | 2/2 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) |

| Australian Capital Territory | OMFS: 1 | 1/1 (100%) | ENT: 1; RONC: 1; MONC: 1; radiology: 1; pathology: 1 | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Western Australia | ENT: 1 | 1/1 (100%) | ENT: 1; head and neck: 1; OMFS: 1; RONC: 1; MONC: 1; ophthalmology: 1 | 1/1 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Queensland | ENT: 6; RONC: 1 | 6/7 (86%) | ENT: 7; PRS: 5 (1†); OMFS: 3 (1†); RONC: 7; MONC: 7; radiology: 5; nuclear medicine: 2; palliative care: 1; pathology: 3; ophthalmology: 1 (1†) | 6/7 (3†) (86%) | 6/7 (3‡) (86%) | 0/7 (0%) |

†, centres who organised OPGs on a case-by-case basis; ‡, centres with non-routine dental practitioner follow up, requiring additional referral externally. ENT, Ear, Nose, and Throat; MONC, Medical Oncology; OMFS, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon; OPG, orthopantomogram; ORN, osteoradionecrosis; PRS, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon; RONC, Radiation Oncology.

Overall attendance of medical subspecialties is listed in Tables 1,2, with dental practitioners including Dentists, Prosthodontics, and Specialist Dental Practitioners, all in addition to OMFS surgeons who are recognised by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) as both medical and dental surgical specialists. ENT, Radiation Oncology (RONC), Medical Oncology (MONC), and Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon (PRS) demonstrated consistent attendance rates, with additional OMFS attendance shown in the majority (52%) of centres. There was significant heterogeneity in the other medical subspecialties who attended, which was a consistent finding amongst centres. Regular attendance was defined as physical or virtual attendance at each MDT meeting, which varied from weekly to fortnightly depending on when facilities held their MDTs. Additional numbers of Allied Health staff attendance are shown in Table 3, with nursing staff including clinical nurse consultants, liaison officers, nurse unit managers of specific post-operative wards, and theatre bookings officers, with all centres demonstrating regular speech pathologists, dieticians, and dedicated clinical nurses attending.

Table 2

| Subspecialty practitioner | Number [%] |

|---|---|

| Ear Nose and Throat Surgery | 21/21 [100%] |

| Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 11/21 (2†) [52%] |

| Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 19/21 [91%] |

| Head and Neck Surgery | 5/21 [25%] |

| Radiation Oncology | 20/21 [95%] |

| Medical Oncology | 19/21 (1†) [91%] |

| Pathology | 10/21 [50%] |

| Radiology | 14/21 [67%] |

| Nuclear Medicine | 6/21 [29%] |

| Palliative Care | 3/21 (2†) [15%] |

| Ophthalmology | 2/21 (1†) [10%] |

| Neurosurgery | 1/21 (1†) [5%] |

| Anaesthesia | 1/21 [5%] |

| High-Risk Medical Physician | 2/21 [10%] |

| Dental Practitioner | 14/21 [67%] |

†, numbers of those who do not attend regularly, or attended prior to the survey’s completion

Table 3

| Allied health professional | Number [%] |

|---|---|

| Speech Pathology | 19/21 [91%] |

| Multidisciplinary Team Meetings Coordinator | 9/12 [45%] |

| Clinical Nurse | 14/12 [71%] |

| Social Worker | 7/12 [33%] |

| Dietician | 14/12 [71%] |

| Physiotherapist | 3/12 [14%] |

| Exercise Physiologist | 1/12 [5%] |

Table 4 outlines MDT chairperson by speciality, with ENT most commonly at 15/21 (71%). Table 1 further breaks this down and shows that two centres utilised co-chaired meetings between two subspecialties, with one centre rotating between three specialities and another rotating between five specialities.

Table 4

| Medical subspecialty | Number |

|---|---|

| Ear Nose and Throat Surgery | 15 |

| Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 2 |

| Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 1 |

| General Surgery | 2 |

| Radiation Oncology | 5 |

| Medical Oncology | 1 |

H&NC MDT catchment populations ranged from 200,000 to over four million and included patients within their state as well as interstate. All centres had the capacity and ability to discuss patient cases, with patients then being seen in an outpatient clinic setting. Eleven centres have combined physical and virtual attendance on the day of discussion, with other centres discussing patients’ cases followed by a review of patients in a separate clinic.

Discussion

Survey responses demonstrated that multiple centres utilise a multidisciplinary approach to assessing and planning the treatment of H&NC patients. All centres had a multitude of medical as well as allied health staff, in addition to dental practitioners. The presence of dental practitioners at MDTs provides a streamlined pathway for specialised assessment and treatment in a vulnerable patient group. This acts in accordance with current literature and recommendations made by the international medical community. Almost all centres incorporated a dental practitioner within their MDT as well as established referral pathways of care. With the time-sensitive nature of adjuvant radiation therapy (16), this appears to allow for sooner review, treatment, and recovery post-dental treatment so as not to delay adjuvant therapy. Given the often significant burden on the public health system with delays in patient access, the utility of private dental practices helps to bypass this hurdle. However, this presents additional issues of patient cost, and further considerations of cost and overall access are relevant in follow-up appointments.

The use of OPGs was not routinely performed, however, this may reflect the low prevalence of oral cavity and oropharynx malignancies that some centres see, with cutaneous primary malignancies being the most predominant (17). The addition of centres specifying that OPGs are organised on a ‘case-by-case basis’ further suggests that this investigation may not be routinely ordered as it is not routinely required. The ad-hoc availability of this vital investigation appears to contradict the intention to streamline dental assessment and treatments.

ORN is a critical adverse effect of radiation therapy, with the definition being ‘the presence of exposed bone in an irradiated field, which fails to heal within 3–6 months (18,19). Radiation therapy is a common adjuvant modality for H&NC management. Increased risk of ORN has been related to dental conditions associated with systemic factors such as tobacco and alcohol, dental extractions, dental infections, and dental trauma (17). The effects of ORN affect patient health and quality of life, with treatment ranging from surveillance to surgical resection and reconstruction of the affected regions (19). Incidence can range from up to 37% with predisposing factors such as the site of the primary malignancy, radiation technique, radiation dose, and patient’s baseline dental health (19). Rates are suggested to be declining with the development of a better understanding of the aetiology, advances in radiation therapy, better patient education, and multidisciplinary approaches to prevention and management (18). All six centres that monitored rates of ORN reported regular attendance by a dental practitioner, however, the overall low rates of ORN monitoring may suggest a low prioritisation of this adverse outcome which is contrary to what published literature suggests. Dental practitioner involvement and regular review post-operatively may more accurately capture rates of ORN, and the authors recommend that ORN reporting should be standard for head and neck MDTs. Prospectively collecting this data including patient outcomes may improve the understanding of the disease process and improve future patient outcomes.

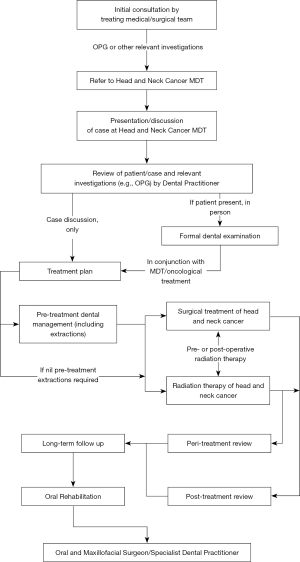

The authors propose in Figure 1, an outline of an idealised dental practitioner referral pathway and involvement in H&NC MDTs within Australia and New Zealand. It is believed that with this standardised pathway, patients requiring timely dental review and treatment and referral to other specialities (such as OMFS) are accommodated promptly. It should be noted that timelines for each review can vary, however, suspicion of ORN at any stage should be dealt with promptly. In addition to this, a defined pathway ensures patients are not lost to follow-up, and oral rehabilitation plays a key part in the patient’s recovery post-treatment.

The impact of treatment is significant and can be challenging for patients and their families. Sequalae is often long-term or permanent including anatomical changes, facial disfigurement, tooth loss, xerostomia, radiation caries, trismus, ORN, and dysphagia, which in turn negatively impact their nutrition, physical health, and psychosocial well-being (20,21). This further highlights the importance of peri-treatment review in patients receiving radiation therapy, as per Figure 1. Oral health and dentition are subspecialty fields that require specific knowledge of pathologies and care. Challenges in clinical assessments include case identification, pain source, and differentiation of the clinical signs of initial ORN compared to other side effects resulting from radiation therapy (18). ORN treatment is difficult and often involves combined therapies including clinical surveillance, and medical and surgical treatment (18). Vigilant clinical review is even more important given the difficulty in radiological diagnosis of ORN due to often non-specific signs (18). Given that ORN can be months to years post-therapy, ongoing follow-up for dental health should be in tandem with oncological follow-up.

Several recently published papers suggest that H&NC patients may have poor dentition at baseline, and would benefit from dental assessment as a holistic approach to care rather than purely ORN prophylaxis (14,22,23). These same papers suggested an additional benefit of pre-treatment dental care would also reduce delays in oncological treatment due to treating or recovering from dental interventions (24). A common theme across publications is the lack of producible guidelines due to minimal evidence and regional variability (14,22).

The additional consideration of oral rehabilitation seeks to provide facial tissue support and oral function, including chewing, comfort, appearance, and speech (14,21-24). This is primarily related to the replacement of dentition, with osseointegrated dental implants and fixed or removable prostheses establishing themselves as the primary workhorse (21,22). This process often begins before patients commence adjuvant treatment, with some patients receiving oral rehabilitation immediately or soon post-operatively (21-23). This reflects the complexity of managing head and neck malignancies which extends beyond eradication of the disease.

This study has shown that there is significant variability in patients’ ability to access oral rehabilitation post-treatment. With so much focus already on workup and treatment of the malignancy, further emphasis and resources need to address oral rehabilitation and post-treatment care. The inclusion and involvement of dental practitioners from the beginning of care would directly improve such outcomes. It should be noted that the disparity in dental practitioners in the public system is a barrier for patients to access such services and makes standardised referral pathways difficult given they are often made across healthcare networks and healthcare systems. The data from this paper seeks to promote further studies into dental practitioner attendance and involvement at H&NC MDTs, with emphasis on their influence on rates of ORN and oral rehabilitation and the development of standardised dental referral pathways.

Limitations

A limitation of this study was the 53% (21/40) response rate and the lack of data from New Zealand, which may not be a representative sample. The nature of a cross-sectional study also does not account for previous and future changes in practice not captured during the recruitment period. Although the authors surveyed each site for regular medical and dental practitioner attendance, it was not within the scope of this study to objectively substantiate this attendance with an audit of attendance logs at each site. This data is therefore subject to reporting bias and certain groups including dental practitioner involvement may be over or underrepresented.

Conclusions

The primary aim of this study was to determine the involvement of dental practitioners in H&NC MDTs, and analyse referral pathways for the assessment, treatment and oral rehabilitation of these patients. Most centres had some involvement of a dental practitioner, however, there exists significant heterogeneity in the extent of involvement and referral pathways. Dental review remains an important aspect of head and neck malignancy workup, which can often be overlooked or underestimated in-patient care. The results of this study seek to highlight a potential area of improvement for MDTs, with the authors suggesting a standardised pathway for timely dental review and treatment in head and neck malignancies, as well as an emphasis on ORN reporting and awareness within Australia and New Zealand. Given the well-established link between oral health and ORN, the authors believe that with a standardised model of care for dental practitioner involvement in H&NC MDTs, the impact of this pathology on patients can be reduced in the future.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SQUIRE reporting checklist. Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-53/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-53/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-53/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-53/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Ethical Exemption was applied through, and endorsed by, the Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee, HREC Reference EX/2023/QTDD/100748. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for the publication of this article.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Victoria Government. Achieving best practice cancer care: A guide for implementing multidisciplinary care. Metropolitan Health and Aged Care Services Division; 2007.

- Queensland Health. Good Practice Guide for Boards. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/system-governance/health-system/managing/statutory-agencies/foundations-resources

- Australian Government CA. Benefits of multidisciplinary care Available online: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/clinicians-hub/multidisciplinary-care/all-about-multidisciplinary-care/benefits-of-multidisciplinary-care

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. Multidisciplinary teams: Integrating care in places and neighbourhoods Available online: https://www.scie.org.uk/integrated-care/workforce/role-multidisciplinary-team#downloads

- Queensland Government. Multidisciplinary Team Meeting Guide Available online: https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/priority-areas/clinician-engagement/queensland-clinical-networks/cancer/multidisciplinary-team

- Ministry of Health. Guidance for Implementing High-Quality Multidisciplinary Meetings: Achieving best practice cancer care. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012.

- Australian & New Zealand Head and Neck Society. Multi-Disciplinary Teams in Australia and New Zealand 2023. Available online: https://anzhncs.org/mdt/

- King R, Li C, Lowe D, et al. An audit of dental assessments including orthopantomography and timing of dental extractions before radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Br Dent J 2022;232:38-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Devi S, Singh N. Dental care during and after radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2014;5:117-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCaul LK, Barclay S, Nixon P, et al. Oral prehabilitation for patients with head and neck cancer: getting it right - the Restorative Dentistry-UK consensus on a multidisciplinary approach to oral and dental assessment and planning prior to cancer treatment. Br Dent J 2022;233:794-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalsi H, McCaul LK, Rodriguez JM. The role of primary dental care practitioners in the long-term management of patients treated for head and neck cancer. Br Dent J 2022;233:765-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jawad H, Hodson NA, Nixon PJ. A review of dental treatment of head and neck cancer patients, before, during and after radiotherapy: part 1. Br Dent J 2015;218:65-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haynes DA, Vanison CC, Gillespie MB. The Impact of Dental Care in Head and Neck Cancer Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Laryngoscope 2022;132:45-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Urquhart O, DeLong HR, Ziegler KM, et al. Effect of preradiation dental intervention on incidence of osteoradionecrosis in patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc 2022;153:931-942.e32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore C, McLister C, Cardwell C, et al. Dental caries following radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Oral Oncol 2020;100:104484. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun K, Tan JY, Thomson PJ, et al. Influence of time between surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy on prognosis for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Head Neck 2023;45:2108-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AIHW. Head and neck cancers in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2014.

- Manzano BR, Santaella NG, Oliveira MA, et al. Retrospective study of osteoradionecrosis in the jaws of patients with head and neck cancer. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019;45:21-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acharya S, Pai KM, Acharya S. Risk assessment for osteoradionecrosis of the jaws in patients with head and neck cancer. Med Pharm Rep 2020;93:195-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garner SJ, Patel S, Pollard AJ, et al. Post-treatment evaluation of oral health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients after dental implant rehabilitation. Br Dent J 2023; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laverty DP, Addison O, Wubie BA, et al. Outcomes of implant-based oral rehabilitation in head and neck oncology patients-a retrospective evaluation of a large, single regional service cohort. Int J Implant Dent 2019;5:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald KT, Lyons C, England A, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of osteoradionecrosis (ORN) in Head and Neck cancer patients in Ireland: A 10-year retrospective review. Radiother Oncol 2024;196:110286. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh EZ, Beech N, Johnson NR, et al. The dental management of patients irradiated for head and neck cancer. Br Dent J 2023;234:800-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vosselman N, Alberga J, Witjes MHJ, et al. Prosthodontic rehabilitation of head and neck cancer patients-Challenges and new developments. Oral Dis 2021;27:64-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Chen FJ, Armstrong L, Keenan J. Dental practitioner involvement at head and neck cancer multidisciplinary meetings in Australia. Aust J Otolaryngol 2025;8:17.