Our experience of fish bone foreign bodies in the upper aerodigestive tract: a retrospective cohort study of 1,293 patients

Introduction

Fish bone foreign bodies (FBFB) in the upper aerodigestive tract represent a diagnostic challenge. There is currently little evidence to guide appropriate management. The prevalence of retained FBFB is common, with fish bones accounting for 46–88% of all ingested foreign bodies in adults (1-4). Incidence is higher in regions with high rates of seafood consumption such as coastal regions and many parts of Asia (1,5). Auckland is a coastal city and has a large Asian population (28.2% of Auckland residents) (6). Consumption of fish is common, with an estimated 91% of New Zealand consumers purchasing seafood regularly (7). The vast majority of ingested foreign bodies pass spontaneously without any intervention required (1,8,9). While complication rates are low (3%), they can be serious and include deep space neck infections, haematoma, oesophageal perforation, mediastinitis, tracheoesophageal fistula, lung abscess, pneumothorax, and pseudoaneurysm (1-3).

Patients typically complain of a foreign body sensation and localised pain. Other symptoms include dysphagia, odynophagia, vomiting, retching, and blood-stained saliva (1,2,4). There are varying reports as to the reliability of patient symptoms in detecting a FBFB. Mucosal abrasions can cause discomfort for several days and add to the diagnostic challenge (2). FBFB are commonly found in the palatine tonsils, tongue base, vallecula and piriform fossa (1,3,8,9). FBFB can be removed via direct vision, flexible endoscopy under local anaesthesia, via rigid pharyngo-oesophagoscopy or an external approach under general anaesthesia (3).

The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to evaluate clinical characteristics, imaging modalities, interventions and clinical outcomes of patients presenting to Auckland City Hospital; an adult otorhinolaryngology (ORL) tertiary referral centre, over a 10-year period with a suspected FBFB in the upper aerodigestive tract. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-60/rc).

Methods

Data was obtained from the clinical records department following institutional approval. Records for all patients who presented to the adult emergency department (ED) for ORL review for a possible FBFB in the upper aerodigestive tract between 1 January 2012 and 30 June 2022 were reviewed. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Institutional approval was obtained from the clinical records department for auditing of clinical outcomes. This project has been assessed as out of scope by Health and Disability Ethics Committee (No. 20478). Because of the retrospective nature of the research, the requirement for informed consent was waived. The following demographic data was collected—age, sex, ethnicity. Clinical data that was collected included number of presentations to hospital, symptoms, duration since ingestion, location of symptoms, species of fish, oral cavity examination findings, flexible endoscopy findings, lateral neck X-ray findings, computed tomography (CT) neck findings, and intraoperative findings. Findings of radiological investigations were reported by consultant radiologists. Outcome data included presence of a FBFB, 30-day readmission rate, discharge medications and associated complications. Patients excluded from analysis were those who had a foreign body other than a fish bone removed, those that self-discharged from hospital prior to ORL review, and those with no documentation available for review.

Statistical analysis

Ethnicity was compiled as New Zealand European, Pacific Peoples, Māori, Asian and other ethnicities. Location of symptoms and site of foreign body identified were defined as oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal/laryngeal. Patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics. Accuracy of radiological investigations was determined with sensitivity and sensitivity calculations. Sensitivity and specificity calculations were performed including radiology reports that stated ‘fish bone present’ or ‘possible fish bone present’. All statistical analyses were calculated using Microsoft Excel for Mac version 16.37 software.

Results

There were a total of 1,349 patients presenting with a possible FBFB between January 2012 and June 2022. Fifty-six patients were excluded; non-FBFB (n=6), FBFB removed prior to review (n=8), discharge prior to review (n=15), and missing clinical documentation (n=27). A total of 1,293 patients were subject to the analysis. Patient demographics are summarised in Table 1. Most common presenting symptoms and clinical signs included foreign body sensation (n=1,056, 81.7%) and odynophagia (n=705, 54.5%). These are further characterised in Table 2.

Table 1

| Demographics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 47.5±16.5 |

| Range | 15–98 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 745 (57.6) |

| Male | 548 (42.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Asian | 735 (56.8) |

| New Zealand European | 202 (15.6) |

| Pacific peoples | 185 (14.3) |

| Other ethnicity | 130 (10.1) |

| Māori | 41 (3.2) |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2

| Presenting symptoms and clinical signs | Values, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Foreign body sensation | 1,056 (81.7) |

| Odynophagia | 705 (54.5) |

| Dysphagia | 88 (6.8) |

| Cough | 26 (2.0) |

| Vomiting | 42 (3.2) |

| Drooling | 25 (1.9) |

| Blood-stained saliva | 56 (4.3) |

| Airway distress | 4 (0.3) |

Number of patients with possible FBFB (%) presenting with specific symptoms or clinical signs. Of note none of the patients presenting with airway distress were found to have a FBFB. FBFB, fish bone foreign bodies.

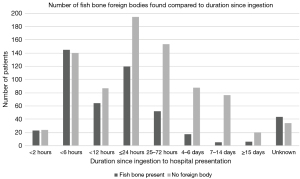

Most patients presented to hospital within 24 hours of ingestion (n=798, 61.7%). Presence of FBFB by duration of symptoms is outlined in Figure 1. Anatomic localisation of symptoms was poorly documented, with data available for 560 patients. Of these, most localised symptoms to the hypopharyngeal/laryngeal region (n=366, 65.4%), 132 (23.6%) localising to the oropharynx, and 62 (11.1%) had non-specific symptoms (Table 3). The most common species of fish ingested was snapper (n=219, 16.9%), followed by salmon (n=81, 6.3%) and cod (n=52, 3.8%).

Table 3

| Level found | Localisation of symptoms, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oropharyngeal (n=132) | Hypopharyngeal/laryngeal (n=366) | Nonspecific (n=62) | Unknown/not documented (n=733) | |

| Oropharyngeal (n=256) | 44 (33.3) | 25 (6.8) | 11 (17.7) | 176 (24.0) |

| Hypopharyngeal (n=209) | 12 (9.1) | 63 (17.2) | 5 (8.1) | 129 (17.6) |

| Unknown (n=11) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.0) |

| Not found (n=817) | 76 (57.6) | 274 (74.9) | 46 (74.2) | 421 (57.4) |

Localisation of symptoms reports the location that the patient identified their foreign body sensation. The level found reflects where the FBFB was actually identified—either on clinical examination with headlight, flexible nasoendoscopy, or in the operating theatre. FBFB, fish bone foreign bodies.

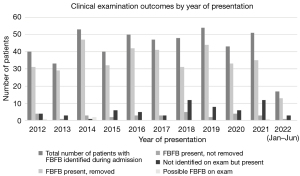

A FBFB was identified in 476 (36.8%) of patients. Methods of removal were: direct vision with headlight (n=112, 23.5%), flexible endoscopy (n=266, 55.9%), and rigid pharyngo-oesophagoscopy under general anaesthesia (n=82, 17.2%). There was no significant difference in the incidence of FBFB identified and removed in ED over time (Figure 2). Three (2.9%) had a FBFB identified at initial assessment but was no longer evident at the time of surgery. Thirteen (2.7%) patients had a FBFB identified on examination but method of retrieval was not clearly documented. Location of FBFB identified was most commonly in the oropharynx (n=256, 52.8%), followed by the hypopharynx/larynx (n=209, 43.9%), with location data unavailable for 11 (2.3%) of FBFB removed; 36.1% (n=467) of patients were discharged with analgesia, and 11.1% (n=143) with antibiotics; 80 patients (6.2%) re-presented to hospital within 30 days due to persisting symptoms. Of these, 25 (31.3%) were subsequently found to have a FBFB.

The localisation of FBFB sensation described by the patients was overall poorly documented, however the patients were able to localise FBFB more accurately in the oropharynx compared to the hypopharynx/larynx. Of note, of the 132 patients localising symptoms to the oropharynx, 44 (33.3%) had a FBFB identified in that region, whilst a further 12 (9.1%) had a FBFB in the hypopharynx/larynx. This is in comparison to the 366 patients who reported a FBFB sensation in the hypopharynx/larynx. Of these, 63 (17.2%) had a FBFB identified in this region, whilst 25 (6.8%) had a FBFB in the oropharynx. Table 3 summarises these findings further.

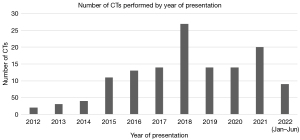

Imaging was performed in 1,022 (79%) patients; 982 (75.9%) patients had a lateral soft tissue neck X-ray, and 131 (10.1%) had a CT neck. Results of clinical and radiological findings are summarised in Table 4. Of the 982 patients who had lateral neck plain films performed, 126 (12.8%) films were reported as having a fish bone present, however only 75 (59.5%) of these patients had a fish bone removed. Furthermore, 769 films were reported as having no foreign body present, whilst 225 (29.3%) of these patients went on to have a FBFB removed. The sensitivity of lateral neck X-rays for accurately identifying a FBFB was low at 31.2% [95% confidence interval (CI): 26.2–36.2%], whilst the specificity (the ability of a lateral neck X-ray to accurately identify the absence of a fish bone) was much higher at 83.1% (95% CI: 80.2–85.9%). The positive predictive value for lateral neck X-rays was 47.9% (95% CI: 41.2–54.6%), whilst the negative predictive value was 70.7% (95% CI: 67.5–74.0%). In comparison, CT scans diagnosed 46 fish bones with 30 (65.2%) of these patients having a FBFB surgically identified and removed; 78 CT scans reported no foreign body present, however 3 of these patients (3.8%) went on to have a FBFB removed. CT scans were more sensitive than lateral neck X-rays (90.1%; 95% CI: 81.1–100%), with comparable specificity (76.5%; 95% CI: 68.1–84.9%). The positive predictive value for CT scans was 56.6% (95% CI: 43.3–69.9%), whilst the negative predictive value was 96.2% (95% CI: 91.9–100%). The number of patients who had CT imaging performed has increased between 2012 and 2015, however the overall trend does not seem to have increased significantly since then (Figure 3).

Table 4

| Examination/investigation findings | All patients, n (%) | Patients with FBFB identified during admission, n (%) | Patients with FBFB in oropharynx, n (%) | Patients with FBFB in hypopharynx/larynx, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical examination | n=1,293 (100.0) | n=476 (100.0) | n=256 (100.0) | n=209 (100.0) |

| Fish bone present | 409 (31.6) | 409 (85.9) | 254 (99.2) | 147 (70.3) |

| Possible fish bone | 9 (0.7) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) |

| No fish bone | 875 (67.7) | 63 (13.2) | 0 | 60 (28.7) |

| Lateral neck X-ray | n=982 (75.9) | n=327 (68.7) | n=164 (64.1) | n=157 (75.1) |

| Fish bone present | 126 (12.8) | 75 (22.9) | 18 (11.0) | 52 (33.1) |

| Possible fish bone | 87 (8.9) | 27 (8.3) | 6 (3.7) | 21 (13.4) |

| No fish bone | 769 (78.3) | 225 (68.8) | 140 (85.4) | 84 (53.5) |

| CT neck | n=131 (10.1) | n=33 (6.9) | n=7 (2.7) | n=24 (11.5) |

| Fish bone present | 46 (35.1) | 30 (90.9) | 5 (71.4) | 23 (95.8) |

| Possible fish bone | 7 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No fish bone | 78 (59.5) | 3 (9.1) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (4.2) |

| Intraoperative findings | n=138 (10.7) | n=85 (17.9) | n=5 (2.0) | n=78 (37.3) |

| Fish bone present | 82 (59.4) | 82 (96.5) | 4 (80.0) | 76 (97.4) |

| Possible fish bone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No fish bone | 56 (40.6) | 3* (3.4) | 1 (20.0) | 2* (2.6) |

*, 2× removed after second return to theatre. Reported findings of examinations and investigations. The indication of the presence of a fish bone does not necessarily mean it was removed. For example, a clinician may be able to accurately identify the presence of a fish bone on clinical examination, but be unable to remove it; therefore, requiring intraoperative removal of the bone. Patients have been further divided into those who had a FBFB identified during their admission, as well as those where data was available on the location it was removed from. CT, computed tomography; FBFB, fish bone foreign bodies.

When considering the location of the foreign body identified, there was a difference in both accuracy of clinical examination findings and radiological findings between the two groups (Table 4). Of the 256 patients that had a FBFB removed from the oropharynx, 99.2% (n=254) were identified on clinical examination; 64.1% of these patients also had a lateral neck X-ray performed; 85.4% (n=140) of these did not identify a FBFB. Only a small proportion of these patients had CT imaging (n=7, 2.7%) or intraoperative management (n=5, 2.0%); 71.4% (n=5) of patients with a FBFB identified in the oropharynx, who had a CT scan as part of their management, had the FBFB diagnosed on imaging; 80.0% (n=4) requiring operative management had a FBFB identified. In contrast, of the 209 patients who had a FBFB removed from the hypopharynx/larynx 70.3% (n=147) were diagnosed on clinical examination; 157 (75.1%) had an X-ray performed, with only 52 (33.1%) diagnosed on lateral neck X-rays, compared to 23 (95.8%) on CT imaging; 97.4% (n=76) of those requiring intraoperative management had a FBFB identified.

One hundred and thirty-eight (10.7%) patients required an examination under anaesthesia (EUA) during their hospital admission. Of these, 82 (59.4%) had a FBFB identified and removed; 56 (40.6%) did not have a FBFB identified on EUA. Of note, 3 of these patients went on to have a FBFB identified during admission, with 2 patients requiring a second EUA (Table 4).

In comparison to the sensitivities of the cohort as a whole, lateral neck X-rays have a lower sensitivity when the FBFB is located in the oropharynx compared to the hypopharynx/larynx [14.6% (95% CI: 9.2–20.0%) and 46.5% (95% CI: 38.7–54.2%) respectively]. However, CT scans have much higher sensitivity—71.4% (95% CI: 38.0–100%) for oropharynx, 95.8% (95% CI: 87.8–100%) for hypopharynx/larynx.

Overall complication rates were low. Of note 8 (0.6%) patients had abscesses, 5 (0.3%) had oesophageal perforations, 4 (0.2%) had oedema requiring steroids, 1 (0.1%) had a rash presumed secondary to cophenylcaine spray. There were 3 (0.2%) cases of extraluminal foreign bodies in the soft tissues of the neck; one deep to sternocleidomastoid, one within the thyroid, and one superior to the brachiocephalic vein. Two (0.2%) patients were incidentally diagnosed with cancer during their admission but did not have FBFB identified.

Discussion

This study highlights the diagnostic challenges clinicians face when treating patients with suspected FBFB. The majority of patients presenting will have no foreign body present (63.2% in this cohort). Yet accurate diagnosis is critical due to the risk of significant complications. There is currently no gold standard management algorithm for patients presenting with symptoms and signs of FBFB.

Our cohort is one of the largest presented in the literature to date. With a mean age of 47.5 years, higher prevalence in females (57.6%), and most patients being of Asian ethnicity (56.7%), this is consistent with previous literature findings (2). Fish bones were found in similar numbers in the oropharynx (53.8%) and hypopharynx/larynx (43.9%). Most were able to be removed under direct vision or via flexible nasoendoscopy (86.4%). We also found that FBFB were more likely to be present in those that presented <24 hours post-ingestion. This is consistent with previous findings, where reported incidence of FBFB dropped from 60% in less than 12 hours to 20% by 72 hours (2). Figure 2 suggests that the incidence of FBFB removed either under direct vision or flexible nasoendoscopy has not significantly changed over time. Whilst the improvement in flexible nasoendoscopy equipment may make FBFB retrieval easier for the treating clinician, our data does not suggest it has significantly impacted overall success rates.

The issues with the use of lateral neck X-rays for identification of FBFB has been discussed in the literature previously. Whilst X-ray imaging is generally more cost effective, has lower ionising radiation doses and is more easily accessible compared to other investigations such as CT imaging, plain X-rays have poor sensitivity and specificity. Previous studies have suggested that plain radiography sensitivity for detecting a FBFB is around 23.5–54.5%, and false negative rates are around 47% (1,2,8,9). Our study is consistent with these findings, with a sensitivity of 31.2% and a false negative rate of 68.8%.

Different species of fish have varying degrees of radio-opacity on plain film. Species such as snapper, salmon and cod (the three most prevalent fish in this cohort) have been reported as radio-opaque, although salmon to a lesser degree (2,10). Studies have previously reported particularly poor sensitivity for identifying fish bones in the oropharynx due to high soft tissue and bone density in this area, with increasing sensitivity in the hypopharynx (2,11). Our findings also reflect this with lateral neck X-rays being more sensitive for FBFB in the hypopharynx/larynx compared to the oropharynx (47.1% and 14.6%).

Our findings show that CT imaging had high diagnostic accuracy (n=46 identified and n=30 removed). CT imaging has been reported at having high reliability for identifying fish bones, with sensitivity between 90–100% and specificity 91–100% (1,2,8,9). Furthermore, positive and negative predictive values of CT are reported at 75% and 97% respectively in the wider literature (1,12). Figure 3 shows an increase in the incidence of CTs performed between 2012 and 2015. This may reflect an increase in accessibility to CTs after this time period. However, since then, the overall incidence of CTs has remained relatively stable (with the exception of 2018), suggesting that clinicians are reserving these investigations for clinical uncertainty rather than routinely requesting scans for all patients.

Whilst our cohort has a large sample size and captures data over a long time period, it is important to acknowledge several limitations with our study. One such limitation was the missing variables in the clinical records—of particular note descriptions of patient localisation of symptoms, species of fish and in some cases where the FBFB was found. Because of this, our subgroups of oropharyngeal FBFB and hypopharyngeal FBFB were smaller than the overall cohort. Furthermore, because only a small number of patients received a CT neck, it should be noted that the sample size used in calculations is smaller for this group compared to those who had a lateral neck X-ray performed. This affects the accuracy of the calculation of sensitivity and specificity.

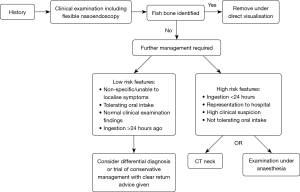

When assessing a patient with a suspected FBFB in the upper aerodigestive tract, we recommend taking a thorough history including the patient’s localisation of symptoms and clinical examination including flexible nasoendoscopy. If a FBFB is not identified on examination, we recommend proceeding to CT imaging or an examination under anaesthetic if there is a short history of ingestion (≤24 hours), the patient has represented to hospital, or there is a high clinical suspicion. We do not recommend routinely ordering lateral neck X-rays. Furthermore, it is important to note that most patients presenting with suspected fish bones will not have any retained foreign body present suggesting a high incidence of mucosal abrasions (in our cohort 62.5%). A well patient, who is tolerating oral intake, with negative clinical examination can be discharged with a trial of analgesia for 24–48 hours, with advice to return for CT imaging or EUA if symptoms persist. Figure 4 presents an algorithm for the management of patients with a suspected FBFB.

Conclusions

Most patients presenting to this institution with a suspected FBFB in the upper aerodigestive tract had no foreign body identified. The majority of fish bones could be identified and removed by clinical examination alone. FBFB were more likely to be identified after a short duration following ingestion. There is a limited role for lateral neck X-rays due to issues with sensitivity and specificity. CT imaging has a higher diagnostic accuracy. Complications were uncommon although not insignificant, and there were low rates of representation to hospital with persisting symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Auckland District Health Board Research Office and Clinical Records Department for assistance with collating the data required to write this manuscript.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/10.21037/ajo-24-60/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-60/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-60/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-24-60/coif). J.J. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Australian Journal of Otolaryngology from July 2024 to December 2026. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Institutional approval was obtained from the clinical records department for auditing of clinical outcomes. This project has been assessed as out of scope by HDEC (Health and Disability Ethics Committee) board (No. 20478). Because of the retrospective nature of the research, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kim HU. Oroesophageal Fish Bone Foreign Body. Clin Endosc 2016;49:318-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sands NB, Richardson K, Mlynarek A. A bone to pick? Fish bones of the upper aerodigestive tract: review of the literature. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;41:374-80. [PubMed]

- Shishido T, Suzuki J, Ikeda R, et al. Characteristics of fish-bone foreign bodies in the upper aero-digestive tract: The importance of identifying the species of fish. PLoS One 2021;16:e0255947. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klein A, Ovnat-Tamir S, Marom T, et al. Fish Bone Foreign Body: The Role of Imaging. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:110-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai AT, Chow TL, Lee DT, et al. Risk factors predicting the development of complications after foreign body ingestion. Br J Surg 2003;90:1531-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Statistics NZ, “New Zealand Census”, 2018. (Online). Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-place-summaries/auckland-region (Accessed 04 December 2023).

- Ministry for Primary Industries Economic Intelligence Unit, “Ministry for Primary Industries”, November 2019. (Online). Available online: https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/38750-New-Zealand-seafood-consumer-preferences (Accessed 04 December 2023).

- Park S, Choi DS, Shin HS, et al. Fish bone foreign bodies in the pharynx and upper esophagus: evaluation with 64-slice MDCT. Acta Radiol 2014;55:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woo SH, Kim KH. Proposal for methods of diagnosis of fish bone foreign body in the Esophagus. Laryngoscope 2015;125:2472-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar M, Joseph G, Kumar S, et al. Fish bone as a foreign body. J Laryngol Otol 2003;117:568-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu TC, Huang PW, Tung CB. Does plain radiography still have a role in cases of fish bone ingestion in emergency rooms? A retrospective analysis. Emerg Radiol 2021;28:627-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jahshan F, Sela E, Layous E, et al. Clinical criteria for CT scan evaluation of upper digestive tract fishbone. Laryngoscope 2018;128:2467-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Rankin A, Dhambagolla I, Johnston J, Vokes D. Our experience of fish bone foreign bodies in the upper aerodigestive tract: a retrospective cohort study of 1,293 patients. Aust J Otolaryngol 2025;8:20.